Pop-up museums act as an alternative space by marrying the museum’s ethnographic approach with the style and content of contemporary art exhibitions, writes Nilofar Shamim Haja.

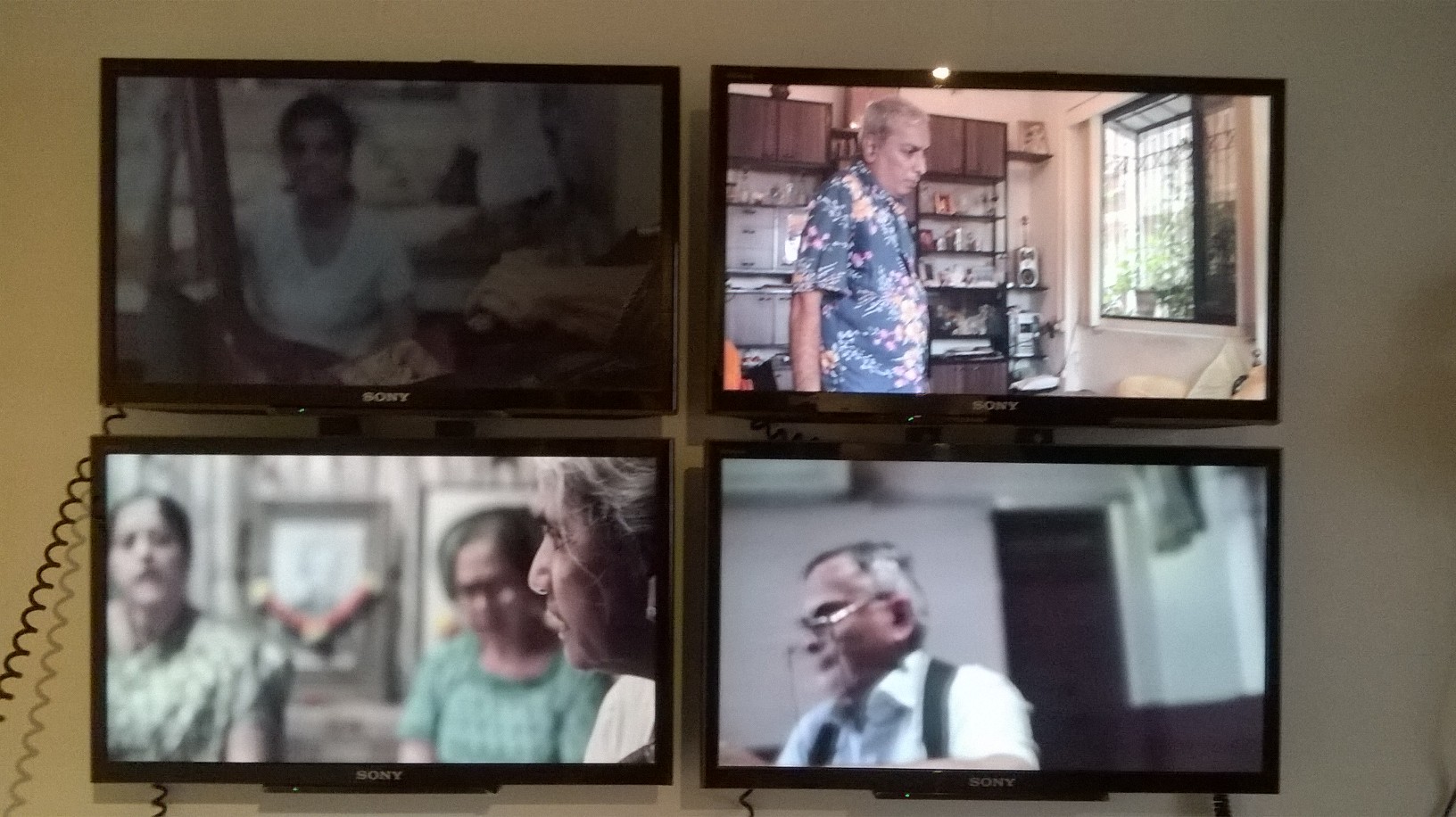

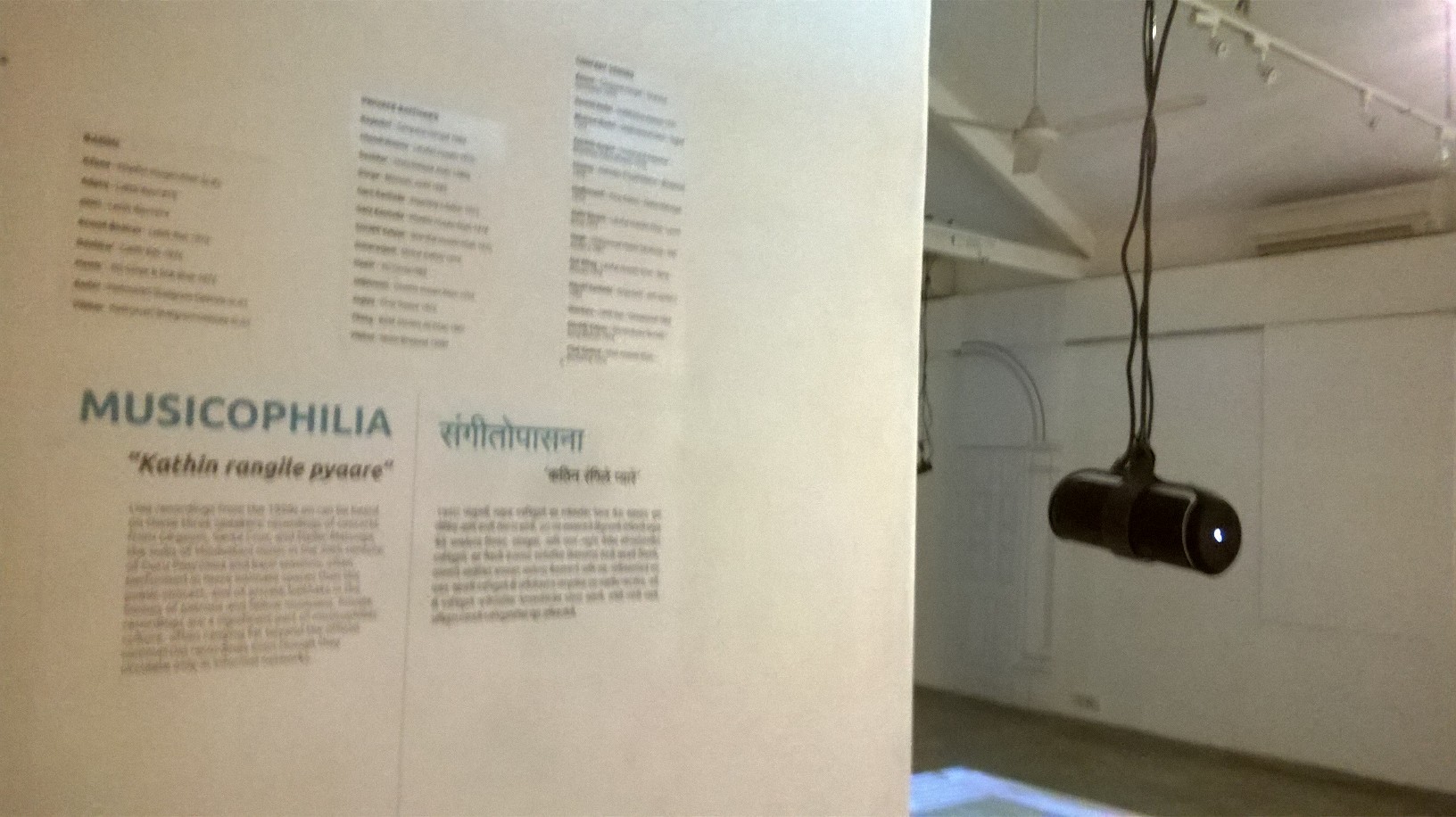

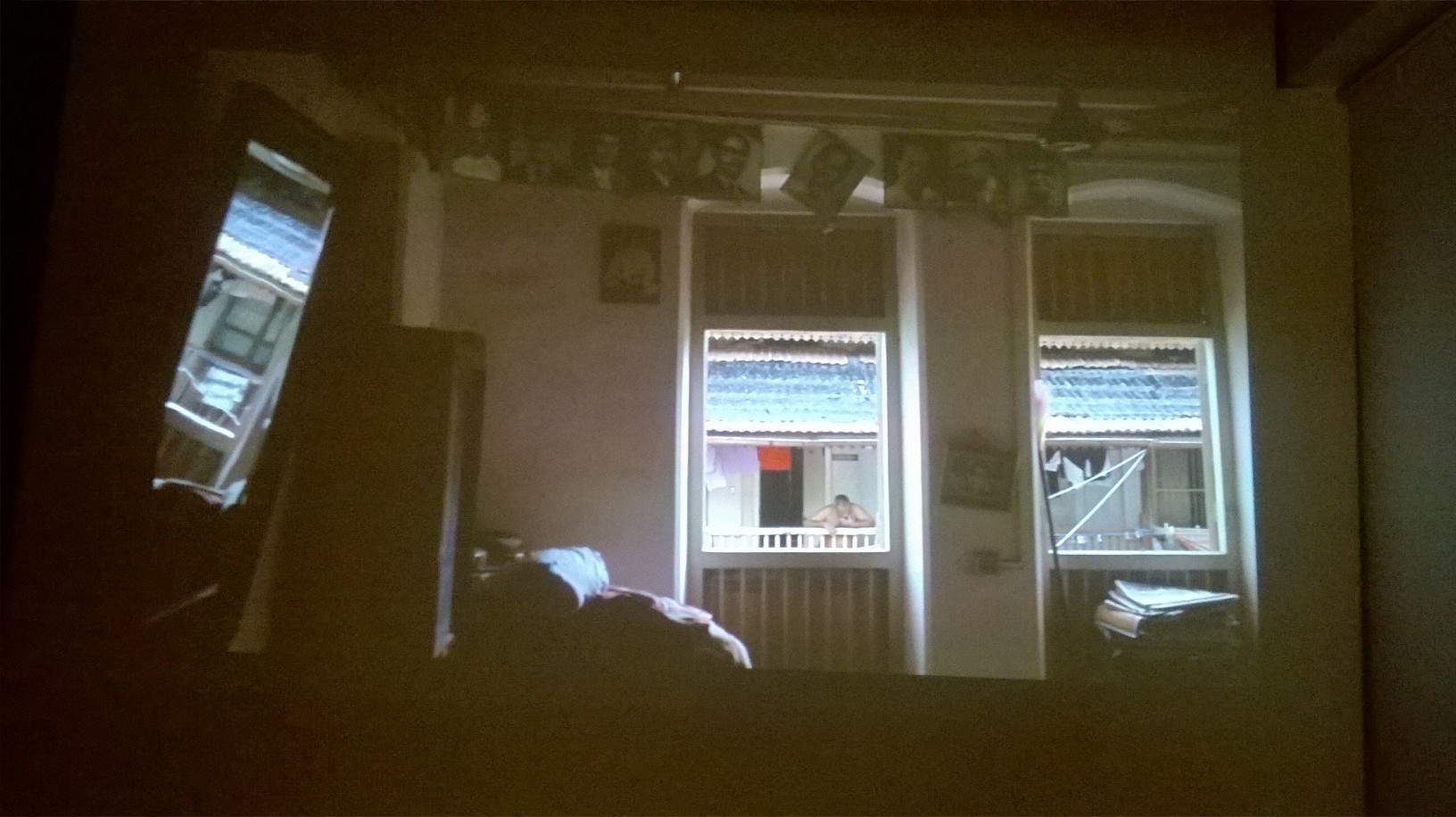

Image: Video installation at the ‘Making Music Making Space’ Hindustani Sangeet in Bombay/Mumbai in Mumbai’s Studio X gallery, June 15-July 7. Photo courtesy author.

Museums and cultural institutions in the Global South work with tight budgets, limited resources, under space constraints and unsteady visitor footfalls. In this blog, we have asked ourselves and our expert contributors two questions, over and over again: why don’t people visit museums in India and how do we increase visitor engagement with museums. Perhaps we can take a cue from ‘pop-up museums,’ a concept that was in its nucleus barely five year ago, but has now gained traction across museums in the United States and Europe.

What are Pop-Up Museums?

Much like pop-up shops (temporary exhibitions and stalls that run for a limited time on the high street, fair or festival), pop-up exhibitions are organised by museums in partnership with local organisations, community centres or citizen associations on site or at an external venue, for a finite period. The pop-up concept relies on the public in curating the show and bringing in objects, stories, oral histories, and other narratives to the exhibition.

The whole purpose is to make this a community-centric event that puts the onus on citizens to be active contributors to the museum space. Here, the museum is unpacked and redefined not only as an institutional or historical site, but as spaces where the community can meet, interact and learn. Themes are far ranging and not limited to the museum’s main collections, although that would certainly help in directing attention toward existing collections.

“Pop Up Museums focus on bringing people together in conversation through stories, art, and objects. They can happen anytime, anywhere, and with any community.” – Pop Up Museum Initiative, kickstarted under the aegis of the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History.

“We were initially attracted to pop-up museums as a way to kick-start conversations about the past in our community. Pop-ups provided a way to bring people, objects, and stories… by creating a museum experience complete with objects, community voices, and visitor engagement” – Katie Spencer, executive director of the Museum of Durham History, who organised a series of pop-up exhibitions prior to the opening of her museum in Durham, North Carolina, United States (Courtesy, the Future of Museums).

“We had a great experience at our PopUp. It was slightly different as we invited a group of students from one of the boy’s schools we have been working with over the years to participate. We visited them at school prior to the session to talk to them about museums, objects and possible themes. They decided on “stories” as a theme, and what I loved was that some of the boys performed a dance/song as their “object”.” – Dr Lynda Kelly, Australian Museum.

Why are Pop-Ups Popular?

Pop-up museum exhibitions generate enthusiasm precisely because the visitors are held responsible for the success of the show. The parameter of success here isn’t about footfalls, but instead focuses on how well the theme is appropriated by the audience. Pop-up museums act as an alternative space to host non-material and difficult to translate concepts and themes (such as the historical notion of violence or ethnic conflicts) by marrying the museum’s ethnographic approach to curation with the style and content of contemporary art exhibitions.

Capturing the features of a long term museum exhibit by allowing the contours of space and time to compress is one of the essential characteristics of ‘pop-up’ exhibitions.

Labels, display and placement are as important in a pop-up show, encouraging visitors to think about how curators devise an exhibition. The point of departure would be in the inclusive nature of a pop-up: In a museum exhibit, curators carry out a selective interpretation of the subject, coloured by their own and the institution’s ethos, selecting objects based on its appeal, recall value, its historical significance from a regional and global standpoint, and other considerations. In a pop-up, the object selection is wide-ranging and as diverse as the community it represents, with each participant eager to convey their own stories associated with the material and eager to learn about the community’s perspective on the history of the subject.

The article cites two exhibitions in Mumbai, “Making Music Making Space” and the “Hermès Horse exhibition” as take-off points for where pop-ups could play an influential role in fostering community-driven cultural initiatives in India.

Making Music Making Space: Mumbai, June-July 2015

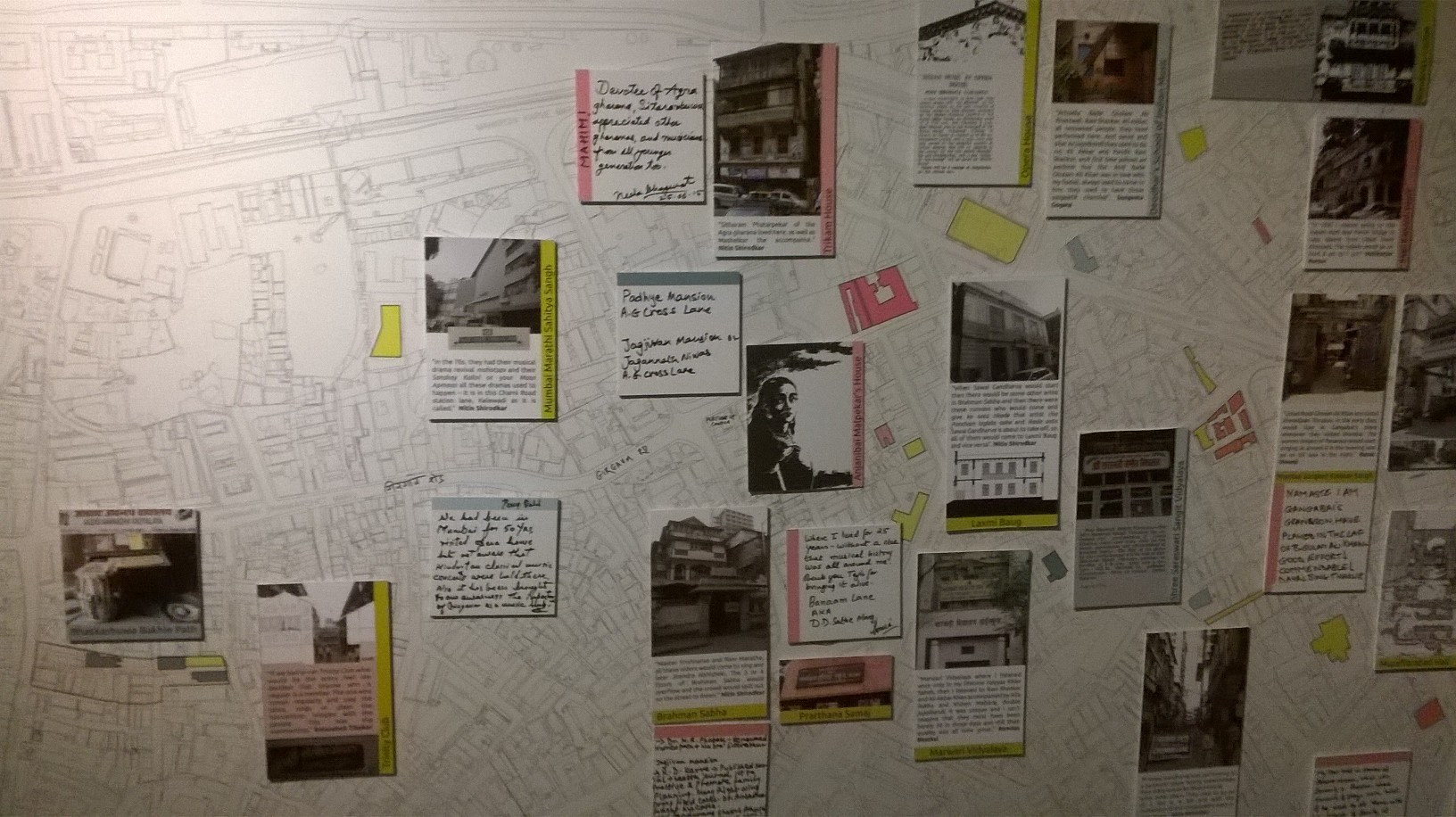

Image Gallery: Relying on a multitude of visual cues that included videos, projections, audio bytes, photographs, maps, advertisement brochures, sticky notes, and digital archives, the exhibition provided an immersive experience for anyone who walked in.

Curated by cultural theorist and curator Tejaswini Niranjana, along with filmmaker Surabhi Sharma, architectural theorist Kaiwan Mehta, architect Sonal Sundararajan and designer Farzan Dalal, the month-long exhibition leveraged the quaint, old-world venue of Studio X at Kitab Mahal, Fort to weave an engaging narrative around the history of Hindustani classical music in erstwhile Bombay.

The Making Music Making Space exhibition included video installations; audio kiosks where we could listen to snippets of music and singing; photographs of singers and people associated with the Sangeet; floor-projection of significant photos highlighting the history of Hindustani Sangeet tradition in Bombay/ Mumbai; a wall map of the important persons and their connection to the city; Apple computers on which visitors could freely browse through video archives, images and other multimedia related to the exhibition.

Ably complemented by curatorial notes about the subject, the space was transformative in its reach and ethnographic approach, literally making a play on its title, Making Making Making Space, by stretching the boundaries of what a traditional art exhibition space can encompass. While the exhibition was executed on the curator’s vision and had no core elements of a pop-up, it could have very easily transitioned into one if the public was invited to contribute through stories, photographs and non-material instances of how Hindustani Sangeet played a role in their histories.

In a way, with the integration of social media into the fabric of exhibition promotions and outreach, one can claim that the public is a contributing actor to the exhibition through their online comments, feedback and conversations, without staking a direct contribution in the curation of the show. This is certainly a line of thought to mull over: could pop-up museum iterations widen its parameters to include digital curation and contributions?

Hermès Horse Exhibition: October 31 to November 30

Image gallery: I participated in a guided tour of the Hermès Mumbai store’s exhibition space, which showcased five generations of curiosities collected by the Dumas family. Photos courtesy: the author.

What elements of this exhibition are akin to a pop-up museum? The exhibition at the French luxury store’s retail outlet at Kala Ghoda, Mumbai had all the earmarks of a classic, museum-inspired curatorial approach with the innovative flourishes of a cutting-edge contemporary arts exhibition. Replete with a wooden rocking pony gilded with decorative bridle from Rajasthan as the centerpiece, the exhibition had 150 pieces, including paintings, sculptures and art pieces that have been part of the Dumas family for two hundred years. The signage, labeling and juxtaposition of the historical legacy against the contemporary luxury avatar of the brand (scarves, jewelry, boots) allows participants a sense of time passing and chronicled by the family.

The exhibition’s curator, Philippe Dumas, artist and member of the fifth generation of the Hermes family, invigorates the space with the right mix of curio objects and narration conveyed through paintings and prints. Visitors can also watch a film by Philippe’s son Émile that documents a horse ride in Paris, during the day and at night, a deft post-modern touch that marks the saddle-makers’ transition from the Old World into the New. What visitors take away from the exhibition is a sense of family and heritage, meticulously documented and highlighted at the Hermes store and evocatively presented through anecdotes by their in-house brand ambassador. This sense of participation is fostered by the brand ambassador encouraging questions and comments that resulted in a richer understanding of not just the brand, but of history, science and technology, the arts, and documentary films in the last two centuries.

The Extraordinary Powers of a Pop-Up

Exhibitions of this nature, with a classic approach to curation cleverly interspersed with a contemporary ethos that focuses on visitor engagement (and outreach through social media) can act as viable templates for independent curators, arts organisations and citizen associations toward hosting a full-blown, pop-up exhibition. The stories can be wide-ranging and topical, ranging from how we deal with climate change, urban migration and renewable energy, to learning about expats in India, Jazz in Mumbai in the 1950s or changing rituals at a festival. Pop-ups can also be organised on short notice, through multiple iterations in a year, with specific audiences or age-groups, and involving multiple stakeholders based on the theme.

The potential to draw a continuous historical narrative from the community and share these stories with the community is easier to stage at a pop-up hosted by the local community center than a full-blown exhibition at our venerable museums, which move at a different pace and adhere to a cultural and national mandate rather than a local one. Museums also operate on longer timelines, typically ideating and organising shows that take anywhere from 6 months to three years to put together. A lot of permissions and bureaucratic hurdles have to be surpassed before a new exhibition opens to the public.

“One of the reasons we started the pop up museum was to challenge the idea that museums have an omnipresent authority over what is and what’s not “valuable.”” – Nora Grant, Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, United States.

The kind of “hack” that can be organised through a pop-up exhibition in local spaces makes use of technology interventions, spatial restructuring, operational and monetary flexibility that is simply unthinkable at our local museums. For instance, if one were to organise a “Night at the Museum” for kids to learn about the history of astronomy and the solar system, museums in the West throw open their doors to parents and children post midnight and organise sleep-ins. While it’s still impossible to broach this subject in India, a pop-up astronomy exhibition organised at the local community center or Natural History Society, can still be organised with the support of the museum and its staff, but under the logistical partnership of the community. Handling boxes (miniature, portable, replicas of collections) can be passed around as learning aids.

The two private exhibitions I have chronicled above hold up one end of the bargain that’s mandatory for pop-up museums to be successful: curating stories and themes that add to a community’s sense of belonging, of history and relevance. The other end calls for these organisations to co-opt the community right from the ideation stage so that all of us get the chance to retell and write the stories that we star in.

Get in touch with Rereeti if you would like to stage a pop-up in your city.

About the Author

Nilofar Haja is Rereeti’s communications officer. She consults with the United Nations-Global Alliance for ICT (UN-GAID) initiated non-profit G3ICT – The Global Initiative for Inclusive ICTs, promoting the rights of persons with disabilities in the digital age. Nilofar is a cultural start-up specialist, with expertise in 360 degree communications strategy for non-profits and cultural organisations looking to scale up their operations. She has a master’s degree in Ancient Indian History, Culture, and Archaeology from the University of Mumbai. Her research interests include protest art, digit communications, urban spaces, contemporary arts, and folklore. She tweets @culture_curate.

Nilofar Haja is Rereeti’s communications officer. She consults with the United Nations-Global Alliance for ICT (UN-GAID) initiated non-profit G3ICT – The Global Initiative for Inclusive ICTs, promoting the rights of persons with disabilities in the digital age. Nilofar is a cultural start-up specialist, with expertise in 360 degree communications strategy for non-profits and cultural organisations looking to scale up their operations. She has a master’s degree in Ancient Indian History, Culture, and Archaeology from the University of Mumbai. Her research interests include protest art, digit communications, urban spaces, contemporary arts, and folklore. She tweets @culture_curate.

Recent Comments